Engagement pods aren’t a new phenomenon. Social media fakefluencers have relied on them since 2016 to boost their popularity online with bought followers, likes, and comments to create the illusion of a large and captivated audience.

However, these social media influencer wannabes aren’t the only ones leveraging the power of engagement pods to get noticed online. Some political and nation-state cells have weaponized engagement pods to spread disinformation and manipulate people far and wide.

We sat down with Barry Hurd, a fractional chief digital and marketing officer specializing in cyber intelligence throughout his career, to discuss the impact these disinformation networks have on everything from election outcomes to public policy.

What is an engagement pod?

Engagement pods are groups of social media users who have agreed to systematically interact with each other’s content. Most social media platforms use engagement metrics to determine popularity and relevance, which drives some users to use the power of pods to artificially boost their visibility online.

Instagram indirectly caused the issue in 2016 when it first changed its algorithm to favor content creators with large followings, likes, and shares. The disease has now spread to other digital platforms, including the professional networking site LinkedIn.

The size of engagement pods varies. Some have thousands of members and deploy automated tools that essentially take over a person’s social media account to fulfill other pod members’ requests for engagement on their posts.

Daniel Hall, a data analyst and founder of Spot-A-Pod said a key characteristic of engagement pods is their coordinated action. New likes, comments, and shares appear within seconds on posts once users submit a request to an engagement pod.

As bad as this type of engagement pod is, Hurd said others are exploiting the tools for more nefarious reasons. “People on LinkedIn call them pods, but people in cyber security and crisis communications call them disinformation networks,” he said. “I think the term LinkedIn Pod doesn’t convey the seriousness of how bad some pods are.”

How do nation-states exploit engagement pods?

The spread of disinformation in the digital age has become increasingly sophisticated. Malicious actors constantly adapt their methods to exploit the vulnerabilities of social media platforms and human psychology.

Engagement pods, originally designed as a marketing tool, have emerged as a powerful weapon in the arsenal of those seeking to manipulate public opinion and undermine democratic processes. They excel quickly at spreading false or misleading information across social media platforms through:

- Instant engagement. Pod members immediately interact with new posts, triggering algorithms to perceive the content as highly engaging and worthy of wider distribution.

- Cross-platform seeding. Disinformation is often spread across multiple platforms simultaneously, with pod members coordinating to share and engage with content on various social media sites.

- Time-sensitive exploitation. Pods can capitalize on breaking news or trending topics by quickly pushing out false narratives before fact-checkers or authoritative sources can respond.

- Layered distribution. Information is often spread in waves, with initial posts followed by seemingly corroborating evidence from different sources—often other pod members—creating the illusion of credibility.

Hurd tracks several political and nation-state cells spreading disinformation on social media platforms like LinkedIn. While some may use pods to boost visibility, it’s not the only way these nefarious actors manipulate the tools to do their bidding. “Sometimes, they just want to use the pod system to validate the profiles they’ve created, especially if it’s 100% fake,” Hurd said. “They want the connections and endorsements and the interaction to appear real. They’re happy to use other people’s platforms for their purposes.”

He said it’s easy to set up a few hundred fake LinkedIn accounts on the dark web with all sorts of requirements handled for security checks. “Especially with AI toolsets, the speed to launch a profile farm with 500 to 1,000 profiles has, unfortunately, become too easy,” he said.

Once the profiles look legitimate, then the scammers behind them can use them for other purposes besides spreading disinformation. On LinkedIn, one of the big trends is nation-state actors from China and Russia using pods to commit fraud.

“When they have enough engagement that you think they’re real or in your industry and you want to connect with them, the chances of you opening an attachment or downloading a document from them increases,” Hurd said. “Do that, and it enables them to hack into your account and steal data and any other sensitive information they want.”

Seeing isn’t always believing

Another way some of these nation-states use fake LinkedIn profiles and engagement pods is to commit employment fraud. LinkedIn is a primary tool for achieving their goal because they can use it as a sophisticated social engineering attack vector, targeting executives, vice presidents, and research and development teams.

These bad actors create convincing LinkedIn profiles with endorsements and numerous connections—sometimes built with the help of engagement pods—before launching their campaigns. They rely on several key tactics to achieve their goals.

Sophisticated Profiles

Attackers use fluent business terminology, sector knowledge, and personal references to make their profiles appear legitimate. Here’s where engagement pods can help, Hurd said. “They use pods to get more engagement on their posts but are careful about how much. It really changes the game when you think that seeing 3 to 5 people engaging on a post makes the original poster seem real, and another level where 25 to 100 engagements might raise an alarm for pods.”

These fake profiles might even connect with legitimate people within a company and go through the motions of building a relationship they can later manipulate.

Whaling Attacks

Whaling attacks are a cyberattack strategy that targets high-profile individuals within an organization to steal sensitive information. These are usually CEOs, CFOs, or other executives with access to sensitive data.

These nation-state adversaries employ highly targeted content that appeals to these “whales” and use it to leverage information about suppliers or partners of their ideal targets to construct credible communications.

Seeing the person behind these fake profiles isn’t always a good way to judge their legitimacy, Hurd warned. Scammers are using AI tools to manipulate their appearances and voices. He shared an example of a CEO of a company in Asia who received an urgent request from his executive team on a Sunday afternoon. He agreed to jump on a Zoom call with the team, during which time they authorized him to make a $20 million transaction to buy another company.

It wasn’t until the next morning when he arrived at the office that he discovered the executive team hadn’t met with him at all over Zoom. It was scammers using AI tools to impersonate them. “What do you do when this happens?” asked Hurd. “You think you’re on a call with the people that control your company. But seeing isn’t always believing.”

Employment Fraud

Another common tactic by nation-states is applying to open positions with companies they’re targeting for disinformation campaigns. They follow the same strategy for creating a fake profile and making it appear real by using the power of engagement pods to build a following and receive endorsements.

The goal is to apply for positions that either give them direct access—or access to someone with—proprietary or other sensitive data. Risks are particularly high for remote positions within these companies because they’re easier to manipulate with fake employees.

“Hopping on a Zoom call for an interview doesn’t mean the person is real since they can use AI to manipulate their voice or appearance,” warned Hurd. “Seeing isn’t always believing.”

Which social media platforms are most vulnerable to disinformation campaigns?

LinkedIn is one of the most popular social media platforms for nation-states interested in conducting disinformation campaigns or infiltrating contractors that frequently do business with the government. “But there are plenty of fake profiles on WhatsApp and X,” he said. “Facebook doesn’t have the kind of data that’s useful to these criminals, so you won’t find many of them there.”

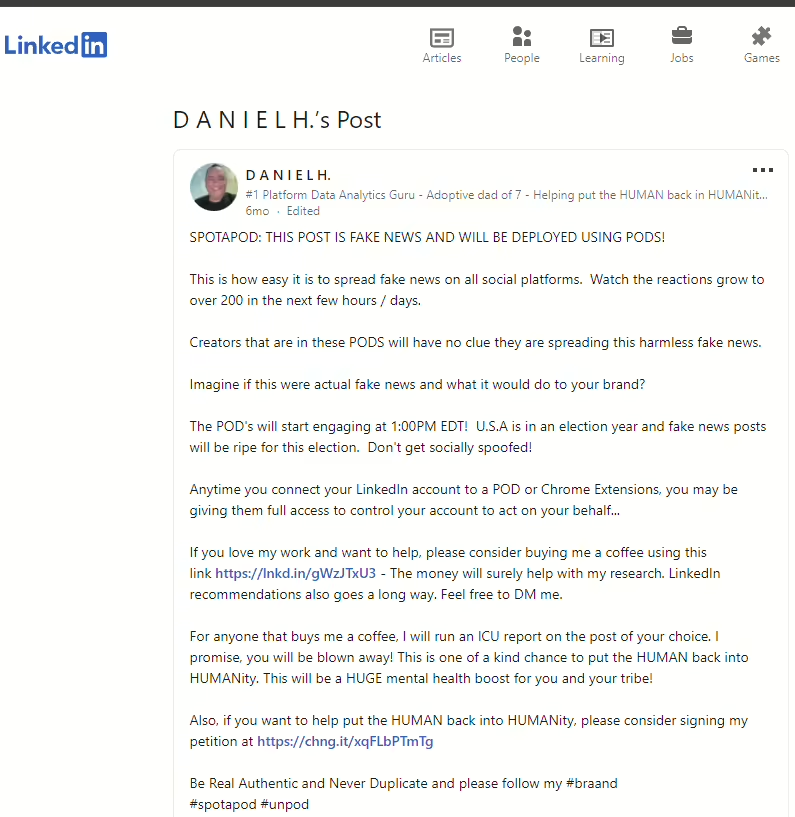

When people use engagement pods, almost all of them are using a Chrome extension that allows the pod service access to their accounts. Hall warns of this frequently when he posts about the dangers of pods and those who manipulate them through his Spot-A-Pod program. “Any time you connect your LinkedIn account to a pod or Chrome extension, you may be giving them full access to control your account to act on your behalf,” said Hall. “Once they have that access, they can literally do anything with your LinkedIn profile. That’s scary and it’s dangerous.”

Hurd advised using caution when interacting with what appears to be a tech startup or another professional in your industry on LinkedIn. What appears on the surface one thing might be a hacking group in Russia or China looking to exploit you. “The technical ability is there to use your account without your permission,” he said. “On the gray end, it’s just liking and posting comments from your account. On the black end of the deal, they can steal your data. All these businesses that think they’re gaming the system (with engagement pods) are installing malware from the Chinese Army.”

How do engagement pods interact with or amplify bot networks spreading disinformation?

Hall has shown how easy it is to use engagement pods to share what he likes to call fake news posts. Here’s how it works. He creates a post on his profile that’s related to something in his industry. He requests engagement through one of the many pods he’s joined as part of his ongoing research. Once engagement starts, he changes the topic of his post to share disinformation instead of what was originally appearing.

“And you have all these pod accounts commenting, liking, and sharing my post that is completely fake news,” Hall said. “Most of these people have no idea they’re sharing fake news because it’s the pod controlling their accounts on their behalf. That’s the quickest way to ruin your professional reputation.”

Hurd called these “one-shot magic bullets” for their ability to quickly spread disinformation. “The accounts eventually get caught and blocked by LinkedIn, but by then, the damage is already done. Millions of people have seen the content.”

LinkedIn deletes it and quietly moves on, which frustrates Hurd and Hall. “They don’t collect the kind of data to track it or make platform users aware of the problem,” Hurd said. “They delete it and sweep it under the carpet so as not to be held liable.”

Masking disinformation with pods

Nation-states and other nefarious actors appreciate the protection engagement pods provide for their disinformation campaigns. They join them and use them to create the illusion of activity online that aligns with their fake profiles.

“They can go onto an influencer’s page and comment on their posts, and no one will notice it’s not from a real person,” said Hurd. “However, it’ll register with LinkedIn’s algorithm that you’re alive and real because it only measures the engagement from your profile.”

It’s harder to use smaller accounts with very little engagement to shield their true purpose because those posters easily recognize when a bot comments on their posts.

What are the real-world implications of disinformation from engagement pods?

While much attention is given to the political ramifications of disinformation campaigns, the business world is increasingly finding itself in the crosshairs of malicious actors using engagement pods. These coordinated efforts can have far-reaching consequences that extend beyond digital platforms to impact an organization’s reputation, operation, and security.

One of the most significant real-world implications of disinformation campaigns using engagement pods is the potential for financial damage, particularly by targeting specific vendors or suppliers within an industry’s supply chain.

“Either they’re specifically targeting a vendor of a corporation that would be impacted by fake news in these pods, or they’re trying to get fake employees into these companies,” Hurd said.

Their strategy might look something like this:

- Reputation assassination. Engagement pods are used to spread false negative information about a particular vendor or supplier. By flooding social media and review platforms with coordinated negative content, these campaigns can severely damage a company’s reputation.

- Market manipulation. False information about a company’s products, financial health, or business practices can lead to stock price fluctuations or loss of investor confidence.

- Contract termination. In severe cases, the spread of disinformation could lead to the termination of contracts or business relationships, causing significant financial losses for the targeted organization.

- Competitive advantage. Competitors might exploit these tactics to gain an edge in the market, potentially leading to long-term shifts in market share and industry dynamics.

How do you protect yourself from disinformation campaigns online?

In the face of growing threats posed by disinformation campaigns and the malicious use of engagement pods to facilitate them, organizations find themselves on the front lines of a new kind of information warfare. The stakes are high, with potential consequences ranging from reputational damage to financial losses to security breaches and operational disruptions.

The challenge is multifaceted and requires a holistic approach. Educating everyone in your organization about how to protect against engagement pods on social media platforms is the most important step in the process, Hurd said.

“They can go through and give all of their employees core social media training to help them identify engagement pod activity,” he said. “They can provide them with a checklist of things to look for when making connections and engagements online. LinkedIn attempts to do that by saying you should only accept connection requests from people you know, but the reality is, most of us are connecting with people we’ve never met before.”

What’s in Hurd’s training checklist?

- A biography check. Research someone you meet on any social media platform to see if you can find traces of them elsewhere. A simple Google search can bring up things like organizations they volunteer with, any published papers, or other professional information to which their name is attached. “If you can’t find another profile or thing about them with their name attached, chances are, they’re not real,” warned Hurd.

- A comment check. Go through and read their last five to 20 comments on other people’s posts, regardless of how old. Look for quality comments that indicate the person possesses a deep knowledge of their industry. “All of the engagement pods use AI chatbots to auto-comment on posts, and the comments are 100% garbage,” Hurd said.

- A core connections check. Look at the people engaging with their posts. If it’s the same core group of three to 15 people always commenting with basic comments that don’t add quality or depth to the conversation, then they’re all likely coming from engagement pods.

Another tell-tale sign that AI bots or fake profiles are about to target you on a social media platform is how they view your profile before engaging. Hurd said most engagement pod platforms are set to review a profile up to three days before trying to connect. “This is the first time you get surveilled by a bot, is when it views your profile. They’ll then send you a boilerplate connection request or DM trying to engage, often saying something like they saw or liked one of your recent posts and thought you should connect.”

Employees who use Chrome extensions or other plug-ins to join engagement pods from their official work devices are most likely violating company policy, Hurd said. “Employment contracts generally include language forbidding third-party access to the computer used for work. It’s probably a good idea to remind employees of this policy as a safeguard.”