Proving defamation seems straightforward until you try it. Someone posts on social media that your business is a fraud. A former colleague tells others you were fired for theft. A podcast host claims you committed a crime you never committed. Your reputation takes a hit, customers disappear, and relationships crumble.

Surely you can sue and win, right?

Not so fast.

While the rise of social media has made it easier than ever to damage someone’s reputation with a few keystrokes, winning a defamation case remains remarkably difficult. The legal bar is set high for good reason. Understanding why requires diving into the complex elements that must be proven in court.

“It can be used as such a sword against public reporting,” says Robyn Kramer, an attorney with Jupiter Legal Advocates in Florida. Despite the apparent simplicity of the concept – someone lied about you and caused harm – defamation cases demand a precise alignment of legal elements that many plaintiffs struggle to satisfy.

The 4 defamation elements you must prove

Defamation laws exist in every state and share the same foundation. To win a defamation case, plaintiffs must prove four distinct elements: a false statement of fact, publication to a third party, fault, and harm to reputation. Miss even one, and your case crumbles.

“The core concepts are similar across jurisdictions,” Kramer explains. “Differences can lie in the degree of intent required and burden of proof.” Some states presume damages for certain types of harmful statements, while others require plaintiffs to prove specific monetary or reputational losses. The venue matters too. Federal courts tend to apply stricter standards than state courts, requiring more detailed pleadings that specify exactly who said what, when, and in what format. These procedural differences can significantly impact a case’s trajectory from the moment it’s filed.

Element 1: A false statement of fact

The first hurdle is establishing that what was said is a verifiable fact, not just someone’s opinion.

“A fact is verifiable about a person and can be proven or disproven. An opinion is subjective,” said Kramer.

Saying “John’s restaurant has rats” is a factual claim that can be investigated and proven true or false. Saying “John’s restaurant serves terrible food” is an opinion that is subjective and protected speech. The statement must also clearly identify the plaintiff. Vague references like “you know who” or broad generalizations like “I hate all realtors” don’t cut it because they don’t single out a specific person or company.

This distinction protects robust public debate. We need the freedom to criticize, question, and express subjective views without fear of litigation. Courts recognize this, which is why they scrutinize whether statements cross the line from protected opinion into actionable false claims.

Element 2: publication to a third party

Here’s where things get interesting. Many people assume defamation requires public broadcasting in a newspaper article, a viral social media post, or a television segment. Not true.

“The interesting thing is, it’s publication to any third party,” Kramer notes. “That means it doesn’t have to be public. So, it doesn’t have to be in the newspaper or social media. It can be something you say to a coworker about someone else or a random person. It just has to be a false statement that is said to a third party.”

In other words, if someone tells one other person a damaging lie about you, that satisfies the publication element. While that might seem strange, the rationale is sound. “Depending on who that third party is, it could cause a lot of problems for you,” Kramer points out. A false statement to your boss, a key client, or a family member can be just as damaging as a public post, even if fewer people hear it.

Element 3: fault (the intent factor)

Fault addresses the speaker’s state of mind when spreading false information. Were they negligent in failing to verify the truth? Or did they act with actual malice, knowing the statement was false or showing reckless disregard for the truth?

“This is a willfulness standard that covers someone’s state of mind,” Kramer explains. “It’s a question of intent. Think of the difference between negligent homicide and murder. Both cause harm, but murder involves purpose or willfulness, while negligent homicide results from carelessness.”

For private citizens suing other private citizens, proving negligence is typically sufficient. But when the plaintiff is a public figure – a celebrity, politician, or prominent businessperson – the standard skyrockets to actual malice. This higher bar reflects our societal interest in protecting robust commentary on public figures and matters of public concern.

“Public people will always be in the news,” Kramer says. “We need the news to be fast. We need journalists to have some flexibility to report what they hear without being sued, and we also want comedians to be able to make jokes about people, so we give some leniency when reporting on or talking about a public person.”

Element 4: harm to reputation

Finally, plaintiffs must demonstrate that the false statement damaged their reputation. This typically means proving concrete consequences, such as lost customers, terminated employment, severed relationships, or other tangible harm.

However, certain statements are so inherently harmful that courts presume damages without requiring specific proof, Kramer said. These are called defamation per se cases.

“Some statements are so harmful that we’ll presume there are damages,” Kramer explains. Accusing someone of having a serious disease like AIDS, claiming they committed a crime, or attacking a business’s core operations – like saying a restaurant has a rat infestation – all fall into this category.

“That’s where a ton of defamation cases come into play today,” Kramer notes. “So many people get online and say things like, ‘this company is a fraud.’ That can be perceived as accusing the company of a crime.”

Historical defamation law also presumed harm for accusations of sexual impropriety, or what the law quaintly termed “unchastity.” Saying someone had an affair or was sleeping with their boss could destroy reputations in an era with different social norms.

Outside these narrow exceptions, plaintiffs must prove real damages. Emotional distress counts, though different states have varying rules about emotional harm, Kramer said. The burden falls squarely on the plaintiff to show real-world consequences of the false statement.

Why government officials have a steeper climb

If proving defamation is already difficult, it becomes exponentially harder when the plaintiff is a government official or public figure. This heightened standard stems from a landmark 1964 Supreme Court case, New York Times v. Sullivan, which fundamentally reshaped defamation law to protect First Amendment freedoms.

The case established that public officials must prove “actual malice” to win defamation claims related to their official conduct. This means demonstrating that the defendant published the false statement while knowing it was false or with reckless disregard for whether it was true. “Actual malice requires proving the person knew the statement was false when they said it,” Kramer explains. “They weren’t just guessing, they knew it was false.”

Reckless disregard means the defendant didn’t even attempt to verify the accuracy of their statement before publishing it. But context matters enormously. Judges consider the circumstances surrounding publication when evaluating recklessness. “Imagine there’s an assassination and the story breaks immediately. If a journalist rushes to publish and makes a factual error because of the urgency of reporting, that context matters when evaluating actual malice,” said Kramer. “Expediency and time pressure can show negligence, but not necessarily reckless disregard for the truth.”

The actual malice standard applies not only to statements about a public figure’s official duties but generally to any statement related to their public role. This makes it exceedingly difficult for politicians and government officials to successfully sue critics.

The evidentiary nightmare

Proving someone’s state of mind is inherently challenging. “It’s difficult to prove that somebody knew something was false. It’s a really high standard,” Kramer acknowledges. “Especially if you’re talking about journalists. You have to ask them a ton of questions about their research. And if they have a source telling them something, maybe that’s good enough.”

Discovery in these cases becomes intensive and invasive. Attorneys must subpoena emails, interview sources, review notes, and reconstruct the defendant’s thought process at the time of publication. Even then, if the defendant consulted sources or conducted research, courts often find that sufficient to defeat actual malice claims, even if the sources turned out to be wrong.

Consider a recent example Kramer cited: Candace Owens accused French President Emmanuel Macron’s wife of being transgender. The Macrons are suing Delaware. According to Kramer, Brigitte Macron’s lawsuit alleges she provided her birth announcement as well as other documentation proving she was assigned female at birth. That same information was allegedly given to Owens before she published her claims, yet she moved forward anyway. This scenario might meet the actual malice standard because Owens allegedly had access to contradictory evidence but published the false claim regardless.

Burden of proof matters

The procedural burden also differs for public figures. In standard civil cases, plaintiffs must prove their case by a “preponderance of the evidence,” essentially, showing their version is more believable than the defendant’s version, or winning by at least 51 percent.

For public figure defamation claims, the standard rises to “clear and convincing evidence.” This sits between the civil preponderance standard and the criminal standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt,” Kramer said. It’s a more substantial hurdle that requires plaintiffs to present significantly stronger evidence and prove the defamation was “highly probable” or “substantially more likely” to have occurred.

The democratization of information

Walk into any attorney’s office today, and you’ll likely hear about an uptick in defamation threats and lawsuits. Kramer attributes this phenomenon to several converging factors.

“We’re so online,” she says. “There are so many opportunities to defame somebody by posting something. And the rise in the number of cases has some political reasons behind them and how polarized we’ve become.”

The democratization of information has a dark side. Online legal resources have made it easier for people to research laws and draft complaints themselves, sometimes without fully understanding the high bar they must clear. The same digital platforms that amplify speech also amplify outrage, making people quicker to threaten legal action when their reputations take a hit.

But there’s another factor at play: the rise of non-traditional media creators who lack journalistic training or ethical standards.

“There are more legit defamation cases now because there are a lot of people – like podcasters – who never went to journalism school and aren’t held to the same ethical standards,” Kramer observes. “Anyone can call themselves a journalist now and some of these people don’t fact-check anything.”

The Alex Jones case illustrates how badly this can go. Jones repeatedly claimed on his show that the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting was a hoax and that the grieving parents were actors. The families sued for defamation, and Jones ultimately lost nearly $1.5 billion in damages across multiple lawsuits. His claims were demonstrably false, he showed reckless disregard for the truth, and the harm to the families was profound and well-documented. All four elements aligned, meeting even the highest standards required in defamation cases.

SLAPP suits and legal bullying

Not all defamation claims are legitimate. Some are filed primarily to silence critics through , drawn-out litigation. These are called SLAPP suits (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation). Pennsylvania is one of the states with an anti-SLAPP statute to protect reporters and everyday citizens.

Florida has similar protections. “The way most of these laws work is if you get sued frivolously, the procedures allow you to have the case dismissed quickly, preventing drawn-out litigation. If the court agrees the defamation claim lacked merit, you can recover your attorneys’ fees.”

Attorneys who file frivolous defamation suits face potential sanctions under Florida’s Rule 57.105, which allows courts to impose penalties when attorneys allege claims with no basis in law or fact. Federal courts have similar rules. Attorneys can also be reported to the state bar for dereliction of duty, Kramer said.

“Sometimes my clients get bogus cease-and-desist letters and I’ll threaten the sending attorney with filing for sanctions against them,” Kramer says. She finds it particularly egregious when attorneys send threatening letters to unrepresented individuals who may not understand their legal rights.

The fee-shifting provisions in anti-SLAPP laws serve an important function: they encourage attorneys to represent defendants who might otherwise be unable to afford legal representation against deep-pocketed plaintiffs wielding lawsuits as weapons.

When intimidation tactics backfire: A local case study

Chris Bonneau, a professor of political science at the University of Pittsburgh and an officer with Together for PR, experienced firsthand how SLAPP tactics are deployed against informed critics. Together for PR is a political organization working to ensure every student gets the education and support they need to thrive in and beyond Pine-Richland.

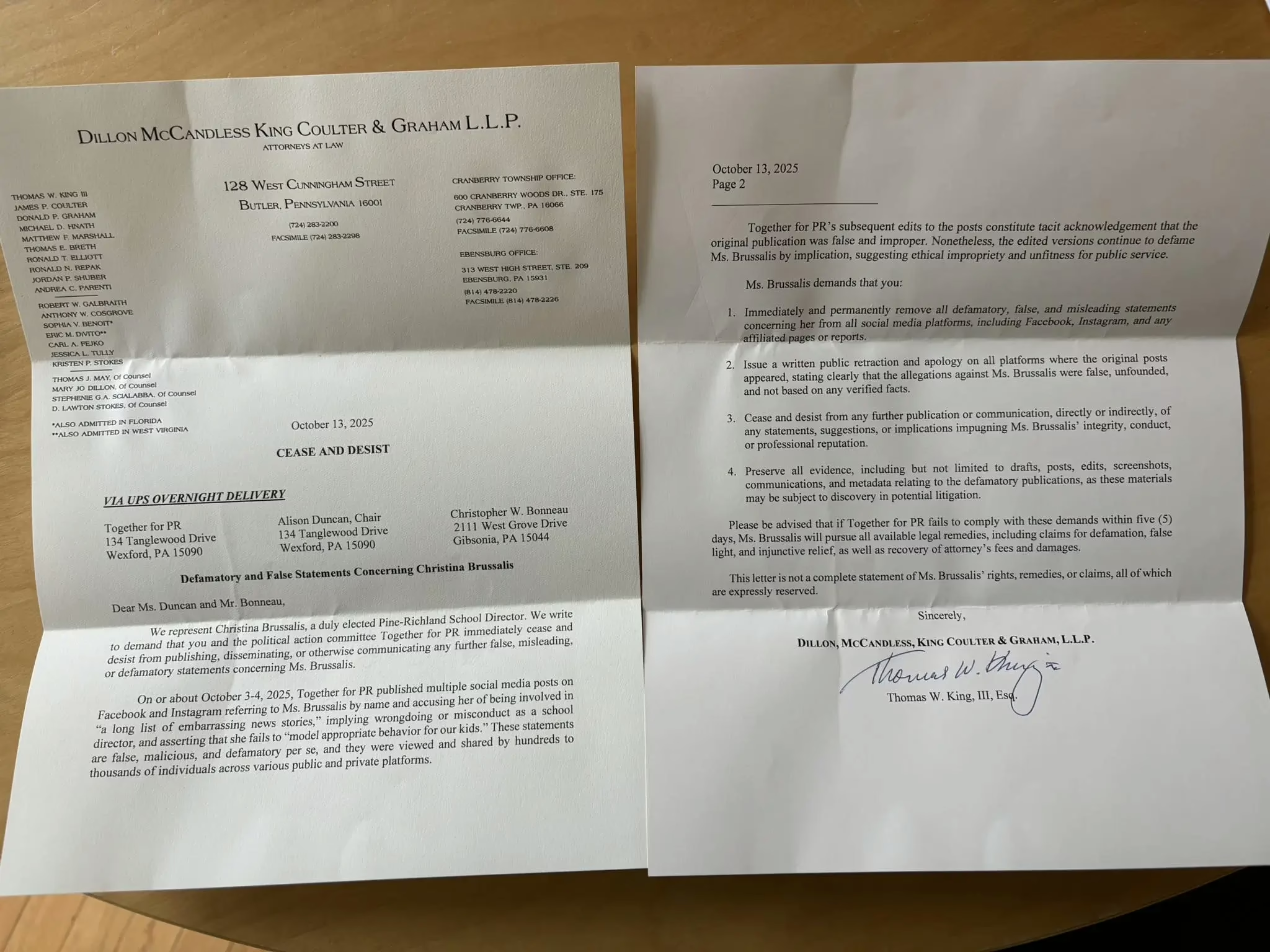

In mid-October, the organization received a cease-and-desist letter from Christina Brussalis, a Pine Richland School Board member and candidate up for re-election, claiming posts made on the organization’s social media page were defamatory and libelous. Brussalis demanded an apology and a retraction of a specific post made to the Together for PR Facebook page.

“We thought it was a joke because we know the law and the standard for public figures. She didn’t meet them,” Bonneau said.

Rather than backing down, the organization made the letter public. In an ironic twist, Brussalis then went onto another social media community group and reposted the very post she claimed was defamatory, generating even more attention for it.

“We altered nothing we did, and we still haven’t been sued,” Bonneau noted. In fact, he’s hoping she’ll file a lawsuit. “I’m not worried about losing. The law is clear. But I’d love to get into discovery. Truth is an absolute defense. And with public figures, it has to rise to actual malice.”

Bonneau views the cease-and-desist letter as part of a broader trend. “It’s an intimidation factor that works on people who don’t know any better.” He was surprised they tried it with him because he knows the law. However, he’s not surprised that more public figures are using this tactic to intimidate critics into silence. He believes it’s spurred by what we see President Donald Trump doing now by suing media he doesn’t like. “And as they settle these frivolous lawsuits, it emboldens more of these kinds of lawsuits.”

His advice to citizen activists and critics is straightforward: “If you do your homework and are confident in what you’re saying and it’s supported by facts, then stay with that. If you made a mistake, then apologize. Mistakes happen, and apologizing shows good faith.”

Bonneau emphasizes the distinction between public and private figures. “With private people you have to be more circumspect. But with people in the public eye, you have a lot more protections. Have the receipts to prove what you’re saying. Not only will the law protect you in PA, but it will also pay your attorney fees.”

As for using lawsuits as a political strategy, Bonneau doesn’t recommend it. “The goal is to have a chilling effect but in the end, it’s not effective. It looks like you’re afraid of what people are saying about you. Instead of just having a debate, you’re trying to stifle it. People generally don’t like to be censored. If I say something you disagree with, then you should counter that, and we should discuss it. It goes against the fundamental nature of political debate and there’s a backlash to that.”

Defending against defamation claims

When facing a defamation lawsuit, defendants have several powerful tools at their disposal. Truth is the ultimate defense. If the statement is accurate, it cannot be defamatory, regardless of how damaging it might be. Opinion remains protected speech. Fair comment on matters of public concern offers additional protection, particularly when discussing government officials or public figures.

“All of it depends on the statement made and how severe the statement was,” Kramer explains. “It’s going to be hard to defend defamation per se statements about a private person. But if the statement was fair game, the defense is going to go well because the plaintiff has the burden of proof. Proving actual malice is difficult.”

Kramer’s defense strategy focuses on examining the contested statement, investigating why the defendant made it, and determining what supporting evidence they had. “From a damages perspective, if the case isn’t defamation per se and the plaintiff suffered no tangible harm – no job loss, no measurable business impact – then what damages really exist?”

Kramer said that’s why it’s funny when an infamous person sues for defamation. “If someone already has a horrible reputation, they’re just adding fuel to the fire if their reputation was already in the gutter.”

The reality of proving defamation

Defamation law walks a tightrope between protecting reputations and preserving free speech. The four-element test – false statement of fact, publication to a third party, fault, and harm to reputation – creates a deliberate barrier that filters out weak claims while allowing truly harmed individuals to seek redress.

For public officials and figures, that barrier rises even higher. The actual malice standard ensures that democracy’s lifeblood, a vigorous debate about those in power, continues flowing even when the discourse gets heated or is mistaken.

Does this mean people can say whatever they want about others without consequence? Absolutely not. But it does mean that before you threaten or file a defamation lawsuit, you should understand the mountain you’ll need to climb. And before you panic over a negative online comment, remember that legal standards exist to separate actionable defamation from protected speech.

In our hyperconnected age where everyone has a platform and opinions spread at lightning speed, understanding these distinctions has never been more important.

Disclaimer: This article provides general information about defamation law and should not be construed as legal advice. Attorney Robyn Kramer of Jupiter Legal Advocates provided legal commentary for educational purposes. If you believe you have been defamed or are facing a defamation claim, consult with a qualified attorney in your jurisdiction.